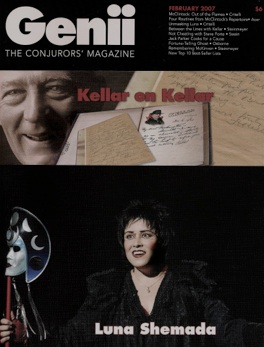

LUNA SHIMADA

Slightly Unmasked

by

Paul Critelli

When interviewing Luna Shimada, if one expects neat, concise answers to simple questions, one will be gratefully mistaken. Her history and artistic views cannot be neatly rolled into a typical Q & A format. She “has a tendency to grow and evolve very rapidly as a person,” and she feels “this need to constantly expand and move forward.” Her open and assertive communication and her artistic journey demonstrate those traits. Luna Shimada may have changed her first name from “Lisa” for several reasons – but, like the “moon,” she is an intense, transforming, and not always comforting presence on stage. Perhaps it was always that way.

Few Magicians can say they were part of an act before they were born, but as her mother was pregnant and assisting her father, Luna had a genetic and pre-natal exposure to show business. “It is in my blood,” she relates, “and everything I saw as a child was just ‘normal’ to me.” Watching all types of variety acts and traveling all over the world gave Luna an extended family of dancers, jugglers, comedians, musicians, and people who she gratefully acknowledges exposed her to the special culture of entertainment. It was the “this is what we do” life that has brought her such joy and such distress.

In 1970 the family was living in London, and Haruo Shimada’s dreams were not being attained. Luna’s father was and is a great dove performer, but the English were not hiring a Japanese Magician doing a “Western” Magic act. Times were bleak as a diet of potatoes and the convenience of coin-operated water faucets made The Shimada Family economic prisoners in a London flat. However, Magic History was about to be made as several seemingly unrelated threads literally came together to make a costume and a legend.

Although Shimada had not considered a “traditional Japanese act,” his Australian wife, Deanna, had often suggested it. However, when his agents began recommending “an Asian act of some kind,” Mrs. Shimada’s advice took on more importance. While in Japan a year earlier, Luna’s mother had seen a performer on a Japanese-style “Gong Show” pulling a large number of parasols, without any deception or artistry, from his traditional hakama. Mrs. Shimada thought the performance was “amazing,” but Mr. Shimada had deemed the “act” ridiculous. Now, faced with a lack of funds and a surplus of advice, Shimada started to listen to his wife. Deanna, a intuitive and creative woman, made a leap out of the box: He magically produces birds, why not parasols? He would need a hakama, but all he had were tuxes and tails. A stop at a martial arts store for a kendo gi, some brocade from a fabric shop, plenty of needles and thread, and the first Shimada costume was created! Shimada-san did work up an act, and he did contact a parasol maker in Tokyo, and he did premier the act in a hotel room in Paris, and, well, the rest ought to be known by every Magician.

The family moved to Mexico in 1971 to do some television work, and Luna, about four years old at the time, saw her father become the veritable “overnight success.” The Parasol Act was gaining great acclaim, and when Shimada premiered it in the USA in 1972, it quickly became the “must have” act of the times. Luna recalls the family shuttling back and forth to California, and names such as Cary Grant, Tony Curtis, and Johnny Carson are remembered along with problems from immigration and a deportation or two. In 1974 the family took up legal residence in California, but mainly as a place to receive mail. Luna can speedily list the world capitals they lived in for varying times, and she was probably a whiz in her correspondence school geography courses.

Luna was to follow in her mother’s footsteps. By the hoary age of eight, Luna was responsible for giving the sound and light cues to the technicians. Shimada would present her as his daughter who knew all the technical requirements, and he would leave. Luna was calling for gels and spots and, if there was a problem, running those same lights during the performance. Most eight-year olds have trouble remembering to feed the cat.

By age twelve, Luna was promoted to an assistant on stage. However, Shimada, then and later, wanted a type of “shadow assistant” who was there only to give him what he needed and take what he produced. Also demanded and delivered at every performance was the perfect execution of all the details which the public never sees. Luna was given all the responsibility with the promise that the Shimada Legacy might someday be hers – not as a performer, in all likelihood, just the name. This was not what Luna wanted to be when she grew up.

The family lived in Japan for a time, and Luna learned traditional movements, dance, and other aspects of Japanese theatre – all so that she could be more of the shadow assistant expected by her father. As anyone who meets Luna can tell you, being a “shadow” anything just is not in her program! She helped make Shimada’s show outstanding, but she wanted to be more than just a helper. Her father “was not into teaching children how to do Magic,” and despite the fact that she had incredible responsibilities – or, perhaps, because of it – her childhood and early adolescence were not as they should have been. Instead of trying out roles and learning, she was working as her father demanded. There was going to be a reckoning.

After five years as an assistant, Luna met James Dimmare, and the two became fast friends and more. Thanks to her years as an integral part of her father’s act, Luna knew great Magic and great assistants, and Dimmare was definitely missing the latter. His star would become one of the brightest in Magic, but at twenty years of age and trying to find the right assistants and blend of Magic, he wisely recognized how Luna’s advice could help him. Her consulting with him did not result in any long-term assistant who really met his performance needs, so after a few months, Luna, in her characteristic no-nonsense way, popped the question: Why don’t I become your assistant?

He, with great insight, accepted, and they lived happily ever after. Not exactly. The initial tsunami would hit when Luna told her father that she was leaving his act to work for a competitor. Luna, perhaps because she has weathered such storms in the past and is in the midst of one now, easily dismissed the year of being shunned. Her partnership with Dimmare was, for the most part, quite satisfying on many levels. She met his perfectionism with her own demanding goals, and she was far more than just a prop handler in the act. Luna’s favorite effect in Magic, which had captivated her since she had seen Richiardi perform it, was The Egg-Lemon-Orange. She fitted it to Dimmare’s style, and she convinced him that it was far better than the thimble manipulation he had been doing. The ten-year partnership was characterized by bookings years in advance, five years of marriage, and “the inevitable breakup.”

At 27, Luna was part of an internationally successful Magic act, again. As before, she was in the secondary role as assistant, despite her huge contributions and creative input and, most importantly, her desire to be a Magician. Her wish of an equal performing partnership was met with Dimmare’s candid and inflexible response: “I cannot and will not share the stage with another Magician.” Luna can be succinct: “We had a wonderful time while it lasted . . . but I wanted more from my life than what I was doing. We amicably broke up, and he helped me with my act.” Perhaps it’s the softening of time, perhaps it’s the self-understanding, perhaps it’s something unconsidered, but in these recollections of the disappointments which she faced, there is no hint of contempt or bitterness. Of course there is regret for missed opportunities, but the sense is that this woman hears something which refuses to let her blame the past for anything.

In Western societies, adolescence is the time for the individual to establish a sense of self and identity by experimenting with different roles and plans for the future. If prevented from doing that, some people have a type of “delayed adolescence” which they may resolve later in their lives. Despite the fact that Luna’s childhood and adolescence were managed to meet many of the needs of others, she retained that core desire to perform Magic. When she left Dimmare, she started doing what had been postponed for ten years, and, happily, her father started encouraging her to become a Magician. He would even give her some of the parasols he’d used. Finally her environment would give her the freedom to be all that she knew she could be! Sort of.

Luna wanted to go “totally contemporary,” and as she was “a rock and roll chick and a wild child,” she took suggestions from McBride, Byrne, and Lupo, infused her act with music from Rush and Yes and Jeff Beck, and upset more than a few people. Spiky hair, black leather boots and bustier, and long finger nails shredding a fan was not the image people expected, but it was what Luna wanted to give them. There was plenty of Magic as in the classic Goth effect of shredded lace to beating heart which bursts into flame which is then restored and glows into a snowstorm. Could anyone ask for anything more?

Actually, they asked for a lot less. Although people expected her to be an ersatz Shimada or Dimmare, Luna wanted to be her own Magician and her own person, and thus began her journey to where she is today. However, old problems often resurface in bizarre ways.

Luna was helping her father in Japan in 1994, doing her show occasionally, and aware that it was a “work in progress.” When some FISM suits asked her to be on the gala show in Yokohama, she was reluctant. It needed more work, and had she accomplished the sense of self and identity upon which she was working – that “delayed adolescence” glitch – she might have not been convinced by her father and others saying “it would be great.”

It was not. The entire FISM event was plagued by problems veteran attendees recall with sardonic humor. Despite the fact that Luna was invited six weeks before the event, she knew that there would have to be major changes with such incidentals as her entire costume, most of the props, and the stage sets. She had to fly back to the States, deal with missed commitments, get back to Japan one week before Yokohama, rehearse as a woman possessed, and be told that she could not have a proper amount of time to tech the show. Her summary of the whole affair: “I was not ready, but I had a lot of guts. I’m not afraid to take big risks, and I will follow through no matter what. How would I feel if I backed out at the last minute? I will disappoint myself. It did turn out to be a nightmarish experience.”

Even with this rather clinical description, Luna recalls that “the hardest part was the way my father took it. It was exceptionally hard for him to see his daughter fail. I felt very bad for him. There were a lot of concerns if I could live up to his name. I understand that, and I don’t hold it against him.” Laughter punctuated her statements. Laughter can be a sign of many things. Some things should remain in the heart.

Luna remained in Japan for about a year working on various projects with her father. It appeared that she was doing what she had done as a teenager, but she now brought the past ten years of creative thinking she’d done with Dimmare to her father’s act. Same sake, different issho. She began to think of Magicians’ daughters who were “part of the act” for twenty or thirty years, and then . . . ? This time the answers to Luna’s questions about what she wanted and where she was going were answered by an assertive, albeit unsure of the details, young woman who knew that she was not a “shadow” or someone behind the scene.

She looks at the FISM act, even though it went poorly, as an act far ahead of its time. It was put away for about a year, but it never really disappeared from her mind. Upon moving back to Las Vegas, Luna received the butt-kicking that only good friends such as Joaquin Ayala and Dimmare can deliver successfully, and she began to “tighten the gaps” of an act she knew she had to do. Her partnership with Jeff McBride helped clarify her “esoteric path” and using symbols in her act became the theme she carries through to this day.

Whether Luna believes in Fate is an open question, but she does hold 1999 as the year her life was impacted in the most amazing way. Having been invited to Vienna to perform, she met Losander from Germany. He was a stranger to her, but she was not unknown to him. He had been at Yokohama, and he had seen her when she was assisting Dimmare. There was an immediate rapport which had no ulterior motives – just that most brilliant Magic that cannot be taught or practiced. The love for each other appeared quickly and it grew intensely. That special Magic led to Tara, their first child in 2001, and Luna decided to take some time away from her Magic on stage to practice that Magic which continues to transform her life. Adam was born in 2005, and he and his sister have given new meaning to their parents’ lives. Luna summed it up by saying, “Motherhood has brought a whole new dimension to my life I never imagined. I feel more grounded now, and I feel an inner peace. My children have taught me how to live in a state of grace. Now that I have returned to the stage, I bring all that love and Magic with me and more.”

When asked what she wants people to think or feel when they see her act, Luna became a bit hesitant, but she quickly recovered and responded, “I don’t know what they are going to think or feel; I left it open to interpretation. I didn’t want to put it into a box. It’s an atmosphere that I am creating, but I want them to have a deeper experience of Magic when they are watching it.”

Luna knows that her Magic is, charitably put, too hip for some rooms. So there is some conflict here as she wants success, but “I want success my way!” She, as do those people of her ilk the rest of us call “artistic and creative,” sees layers and differences and similarities that are, at the same time, universal and idiosyncratic.

In reflecting upon the ten years or so that the act has been developing, Luna reflects that it “had to grow and evolve as I had to grow and evolve. I had a concept what I wanted at the start, but I had not achieved that myself. The act was disjointed and scattered as I was. The act and I are almost like one entity – as I grow and become more well-rounded a person, so does the act. It becomes a personal meditation.”

“I do what I do, and the people who get it, get it, and are appreciative of it; if they don’t get it, that’s OK.” However, this is not said or experienced in an “in your face” sort of way. Rather she invites you to her way of thinking and experiencing what her Magic is, and she really hopes you feel “the poetic experience,” but if you don’t or can’t, she will understand.